Prewar and Postwar

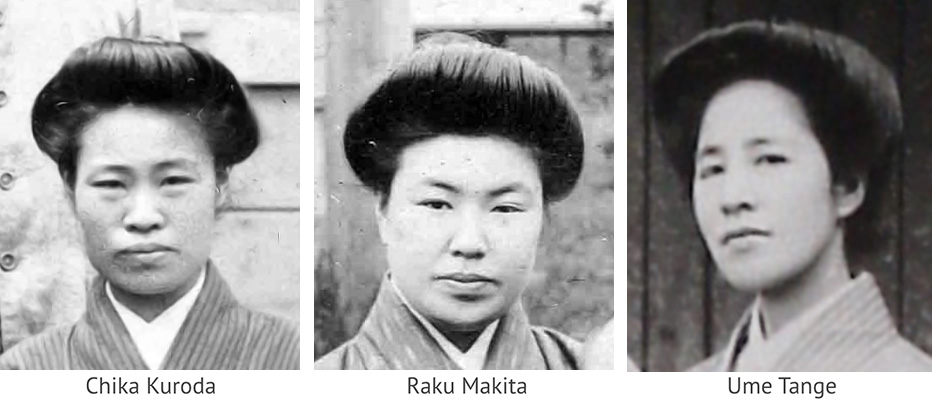

Female Students in Pre-War Period

The next batch of female students did not enroll at Tohoku University until 1922, when two female students joined the Mathematical Institute at the Graduate School of Science. The following year, Tsuya Kubo and Fusa Sakurada became the first female students to enroll in a humanities course at an imperial university, entering the Faculty of Law and Letters. From here onward, it became regular practice for Tohoku University to accept female students. A women’s student association was formed in the early Showa era, bearing the name Shinrankai.

Even as the practice of admitting female students became more mainstream across the country, with the notable exceptions of Tokyo and Kyoto, Tohoku Imperial University continued to boast the highest enrollment of women within the imperial university system. Living up to its reputation as the “academic city,” Sendai attracted female students who aspired to study in the fields of law, literature, and science.

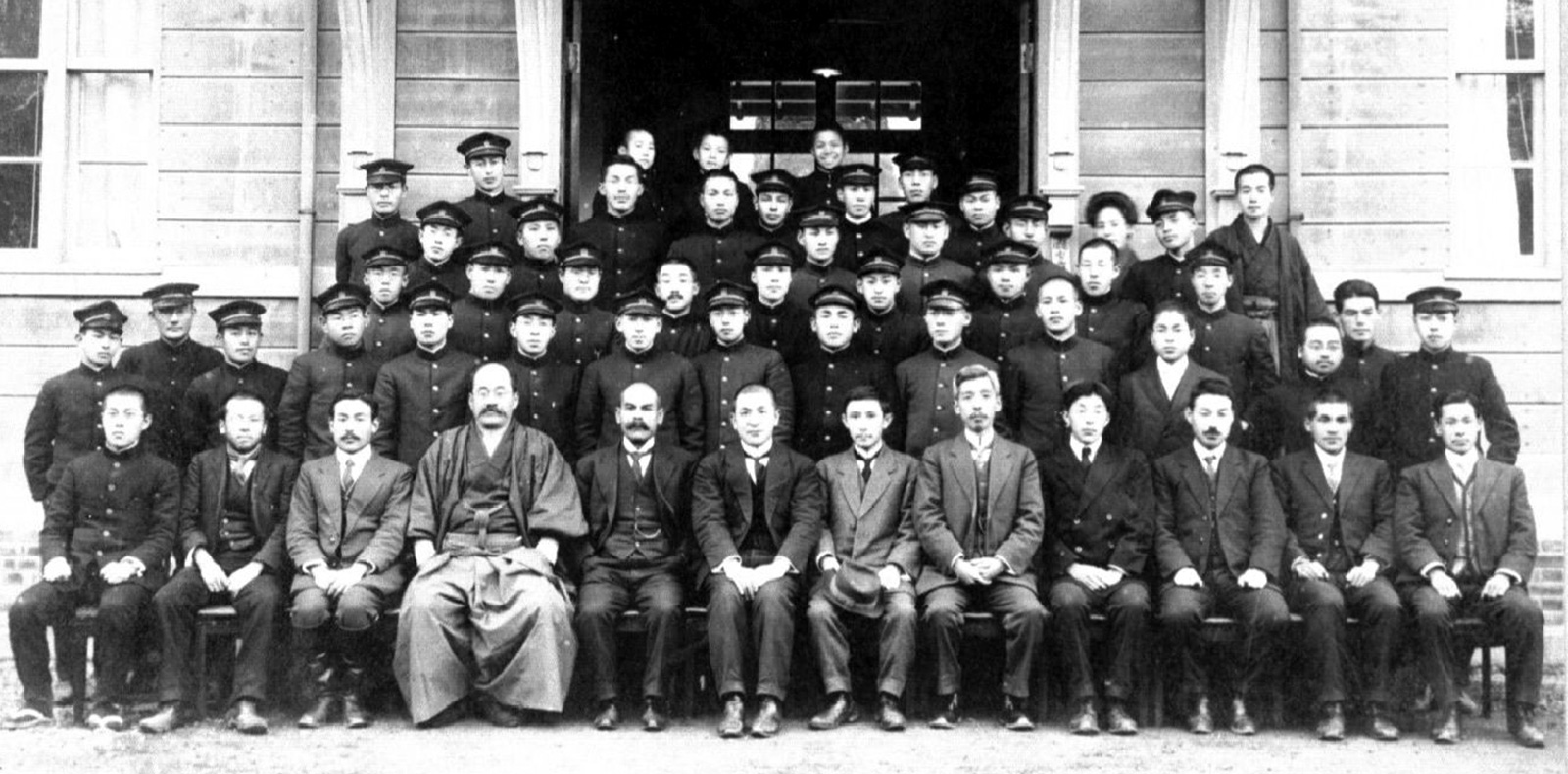

Female university students from the Faculty of Law and Letters in 1940

Female Students in the Post-War Period

The outbreak of World War II paused the gains made by women in the preceding years. Yet in the immediate aftermath of the war, reforms took place that saw the old high school and imperial university system, with their male-orientated entrance exams, abolished. Mixed-education became widely accepted. In 1949, the first year the new system was put into place, Tohoku University welcomed 41 female students. Gradually, women began entering fields such as medicine and engineering.

The enrollment rate of women accelerated during the 1980s. This trend gained further momentum in 2001 when Tohoku University became the first university in the country to establish a Gender Equality Committee. The following year, the university also issued its Declaration for Gender Equality.

Between 2001 and 2021, the percentage of female doctoral students increased from 13.6% to 30.9%, and the percentage of female faculty members increased from 5.7% to 18.4%. While low by international standards, the university’s ongoing commitment to gender equality bore further fruit in 2022 when it launched its Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Promotion Declaration. DEI aims to reduce the gender gap on campus, as well as promote diversity and equity in education so that all students, faculty, and staff can flourish regardless of their gender, age, disability, ethnicity, nationality, or religion.

The first university student gathering for females in 1979