An Ocean of Possibilities

“There’s no hierarchy in my lab. If you need to learn something, you just find the person who knows how to do it best.”

How did you first become interested in Marine Science?

Growing up, I was always by the water. I was born in Canada in a small town on Cape Breton Island known for coalmining and fishing. I also lived on a different island in the Bay of Fundy, where the huge tidal changes fluctuate up to 16 metres a day, twice a day.

Since I was a kid, I was completely fascinated by the dynamics of nature. However, I started off majoring in fine art at university. I happened to make a friend in art school who was from Japan, and I started asking him what it was like there. He said "why don’t you just go?”.

So, I went.

Afterwards, I had the chance to go to the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California and see this amazing jellyfish exhibit. It was in that key moment I thought “this is it!” and decided I had to study jellyfish.

Can you tell us more about your jellyfish research?

I started jellyfish research during my master’s degree in Okinawa. I just loved it there! You can enter the water from almost anywhere and see fish immediately. I ended up naming a deadly species of box jellyfish there. It sparked even more questions about box jellyfish. Why do they sting? How do they sting? How do they get around the world? I specialize in systematics and use molecular phylogenetics and genomics approaches to better understand jellyfishes and to answer these questions.

What is a challenge in your field that you have overcome?

While collecting samples in a foreign country, sometimes you can’t bring them back to Japan and all your work goes to waste. To avoid this problem, I developed a portable, battery-powered kit to sequence environmental DNA or marine organism tissue samples in real time. This means you can do everything onsite - even in austere parts of the ocean with no electricity - and then go home with the data in hand.

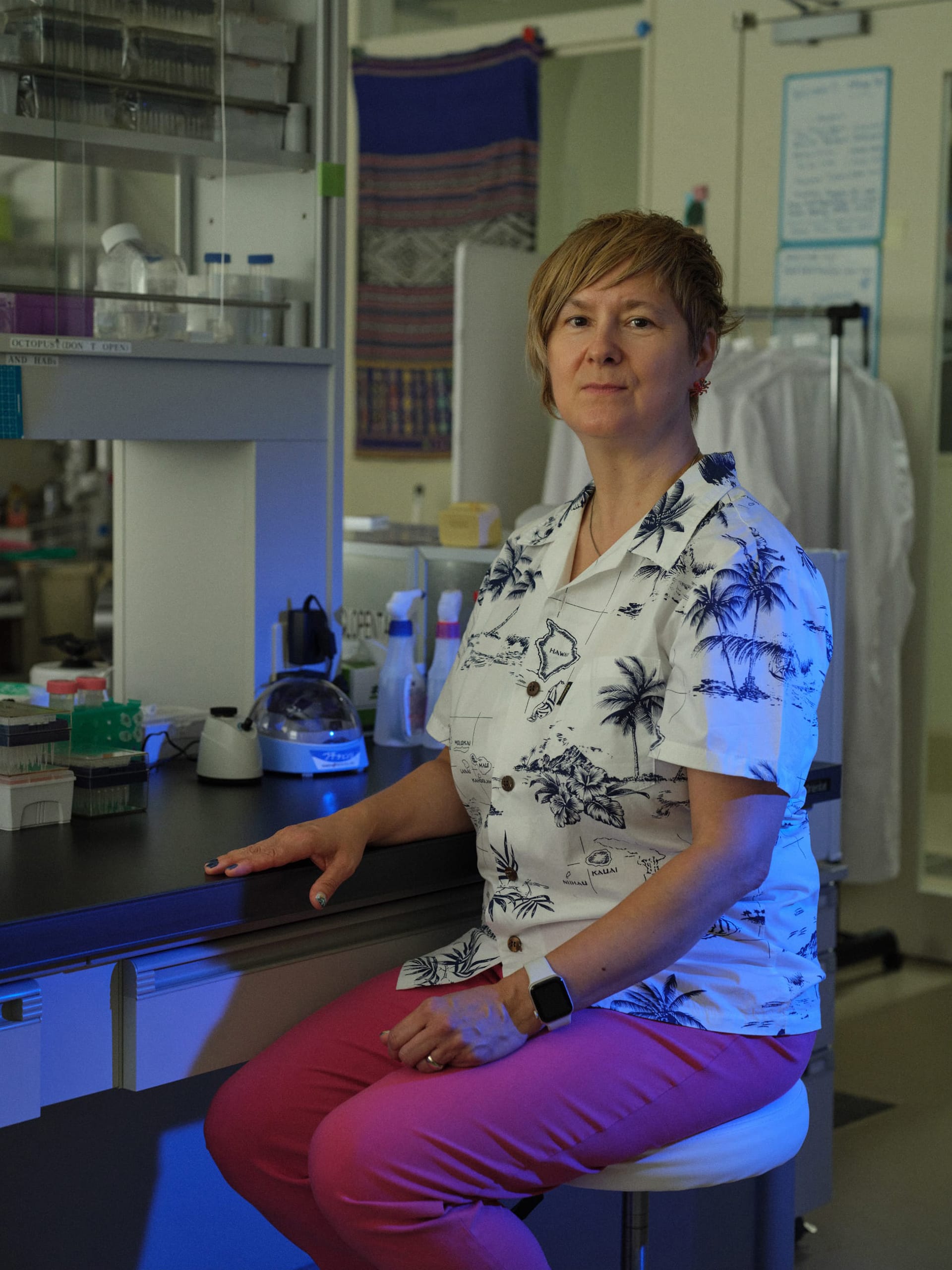

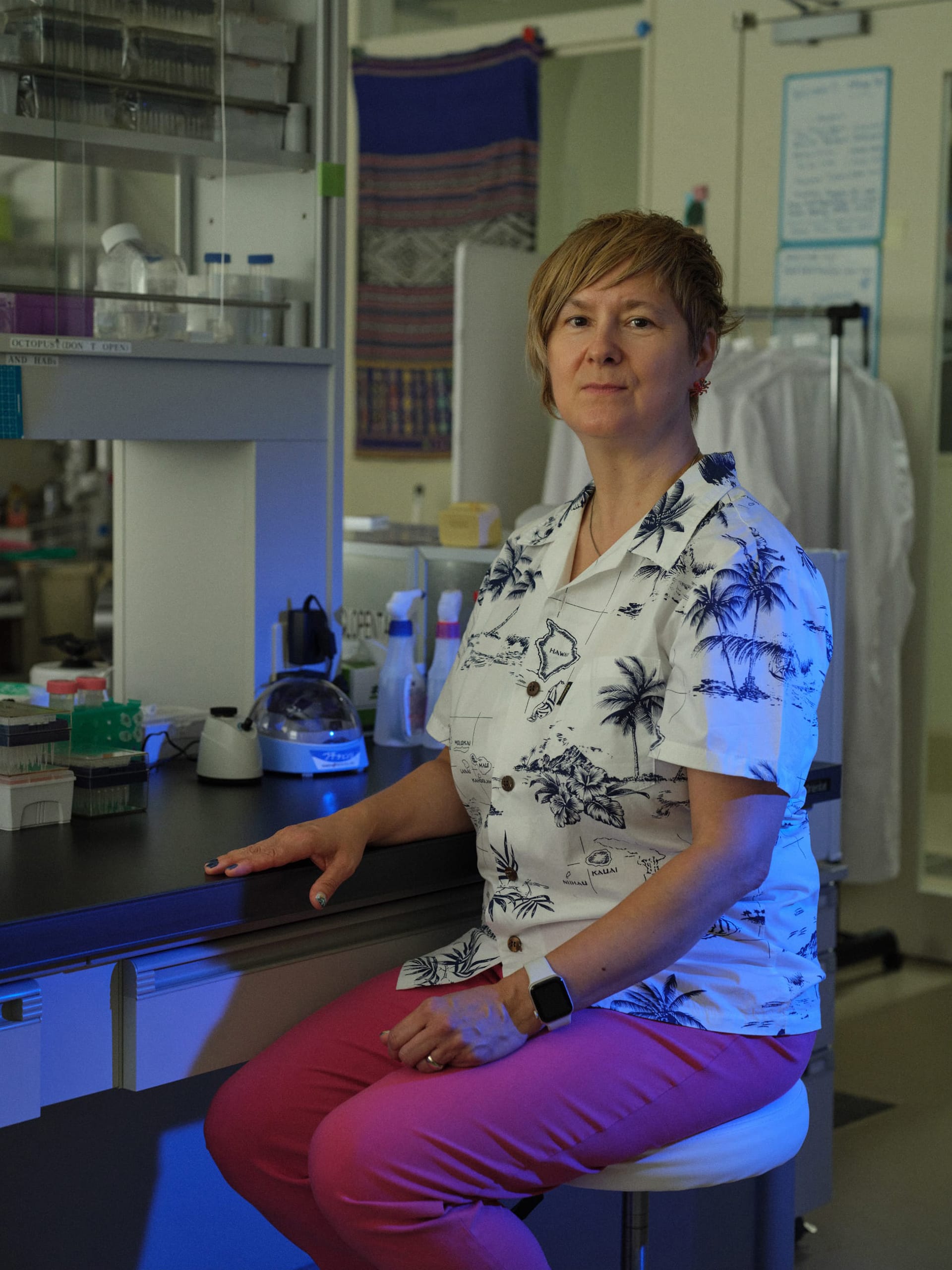

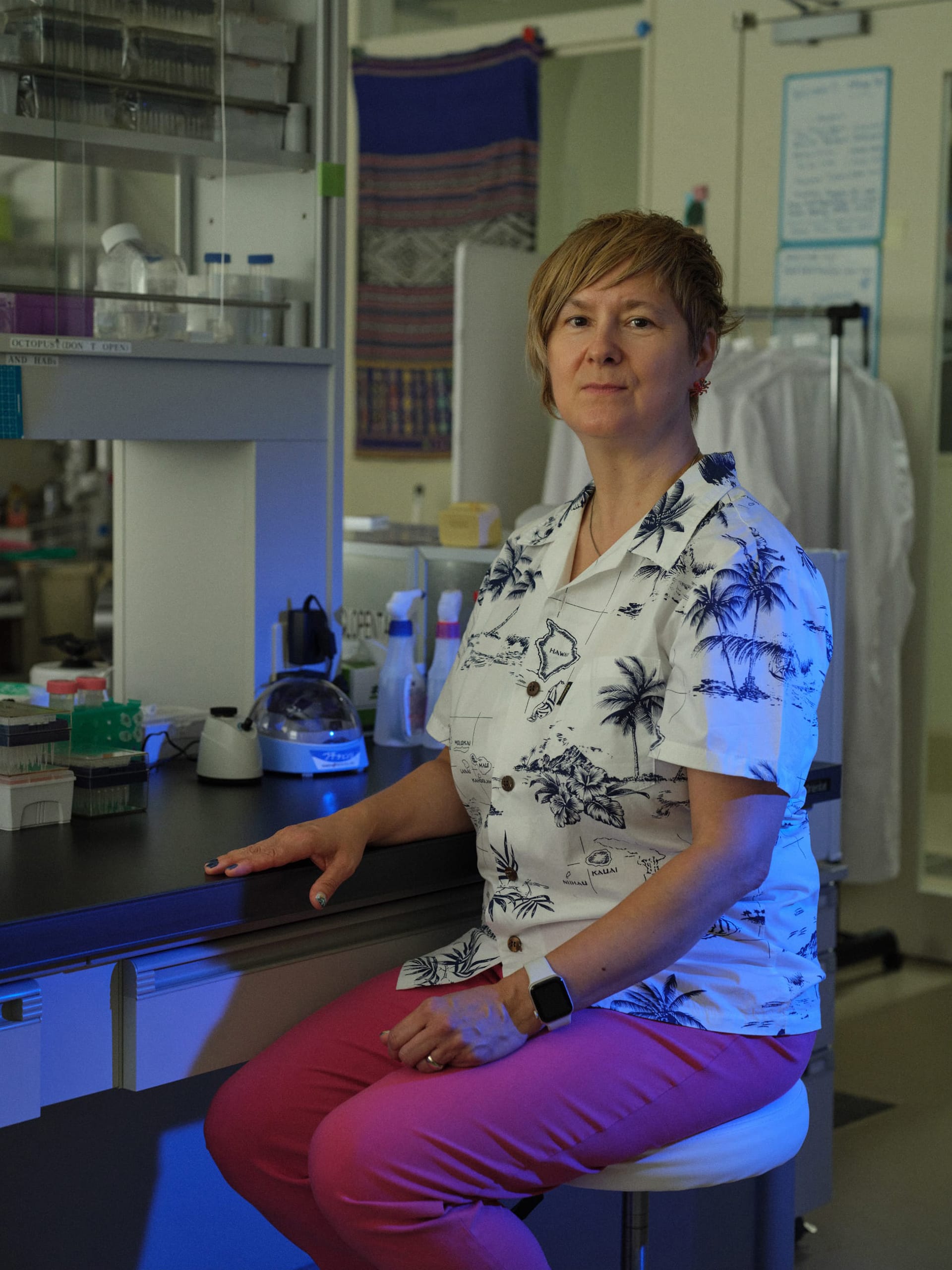

Image courtesy of Tohoku University and Studio Xxingham

Image courtesy of Tohoku University and Studio Xxingham

What is the real-world impact of your research?

My research is connected to local fisheries. For example, the fishery coops allow me to take tissue samples of octopuses or abalone. They give us just a tiny piece of the arm, so that they can still auction them. Fisheries personnel have been very co-operative – even collaborating and co-authoring with us.

In the fishing waters around Tohoku, we’re seeing something that we’ve never seen before. The Kuroshio current brings warm water up from the south in a meandering path to Tohoku each year. However, in the past 2-3 years, that warm water has been coming up more than 400 km north of where it ever was. This creates all kinds of issues for the endemic fauna there. The ecosystems are out of whack, but not a lot has been published yet since this is a recent, ongoing problem in Tohoku. However, some of the seminal papers on these Kuroshio current changes have come out of WPI-AIMEC, co-authored by our scientists in conjunction with JAMSTEC.

Can you tell me what your lab is like?

I have students and postdoctoral researchers from over 10 countries including Japan. We make sure the fourth-year undergraduate students are treated the same as the postdocs - there’s no hierarchy in my lab. If you need to learn something, you just find the person who knows how to do it best. It’s an important system of respect that I am really proud of.

How do you teach your students to go into the field and collect samples?

They just come with me and learn! (laughs) Soon, it will be the first time some of them head on a ship for 15 days in the ocean. They’ll go out and collect samples from dusk until dawn.

To make the process easier, we hired a technician through my Ocean Shot grant to develop a specialized app. Now the students can use their cellphone to log all the data in an organized way.

Outside of the lab, what do you like to do to unwind?

I like going beachcombing. I got back into painting and recently hosted a painting class. When I look back, I see that quite a few of the things I painted back in art school were aquatic scenes.

Photograph: A jar of aquarium glass beads used as a substrate in aquarium tanks. This colourful addition makes the tanks sparkle while providing a surface for beneficial bacteria which promotes biological filtration and improved water quality for the jellyfishes.

After spending a working holiday in the sunny coastal town of Yokosuka as a second-year university student, Dr. Cheryl Ames decided two things: one, that she wanted to study something related to the ocean, and two, that she wanted to do it here in Japan. After completing a master’s degree at The University of the Ryukyus (Okinawa) where her efforts resulted in the discovery of a new box jellyfish species, she did her Ph.D. at the University of Maryland. Her experience as a research associate at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History furthered her knowledge of marine biology and different layers of the ocean, before she made her return to Japan. She now works at Tohoku University as a Professor in the Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences as leads a research unit of WPI-AIMEC. She dives alongside her students in oceans both near (Miyagi and Okinawa) and far (Bonaire, Caribbean) to better understand the drastic changes occurring in ocean ecosystems. As a top expert in jellyfish, her work focuses on unravelling their mysteries at the genomic level. When not in the ocean, you may find her relaxing in nearby onsen towns, painting, or going on a brisk jog to take advantage of Sendai’s relative lack of snow as compared to Canada.

Tohoku University Graduate School of Agricultural Science / Faculty of Agriculture

https://www.agri.tohoku.ac.jp/en/

Romance

of

Research