The Power of Ignorance

They say that knowledge is power,

but ignorance can also be a form of power

Could you tell me how you first became interested in the field of science studies?

I have always been passionate about languages, which is why I chose to study in Canada during high school. There, I learned English, French, and German. Learning new languages opened my world to different literatures and eventually led me to read philosophical texts, which inspired me to pursue French literature and philosophy as an undergraduate. Around the same time, however, the Fukushima nuclear accident occurred. It made me realize that, to gain a more holistic understanding of the human relationship with nature, I also needed to deepen my knowledge of science. Yet, with my background in the humanities, studying the hard sciences proved challenging.

One day, I came across a textbook called An Invitation to the Philosophy of Science. I was astonished to find a book that examined science itself from historical, sociological, and philosophical perspectives. That was when I knew this must be my field.

So what led you to focus on agnotology and the study of ignorance in science?

My journey into the study of ignorance was completely accidental. Towards the end of my master’s, I was casually browsing through course syllabi from overseas universities when one title caught my eye, Agnotology: The History of Knowledge and Ignorance. I had never encountered the term before, and neither had most of my professors. There seemed to be a lot of ignorance surrounding the very study of ignorance itself. I borrowed a book on the subject, and from that day I dove headfirst into the world of agnotology.

Could you provide an example to illustrate agnotology for those unfamiliar—or, dare I say, ignorant—of it?

The tobacco industry is a classic case where ignorance sells. When the link between smoking and lung cancer first emerged, the industry downplayed the scientific evidence. As more studies appeared, they shifted strategy and began funding research into other possible causes of cancer. When the evidence linking cigarettes to cancer became overwhelming, they could no longer deny it. They instead fell back on professing ignorance to the connection. The power of ignorance was perhaps best encapsulated in an internal document from the tobacco industry that stated: “Ignorance is our product.”

Are there any Japan-specific examples?

Minamata disease is one that springs to mind. In the 1950s, when this deadly neurological condition was traced to industrial wastewater from a local chemical plant, the plant’s operators denied any connection, echoing tactics seen in the tobacco industry. “Experts” aligned with the company offered alternative explanations to sow doubt and perpetuate ignorance. Yet activists and local researchers persevered, carefully gathering evidence and challenging the attempts to obscure the truth. Ultimately, their relentless pursuit of the truth led to official recognition of the cause and the cessation of toxic wastewater dumping. Nine years had already passed since the true cause was identified, but without their efforts, ignorance could have caused even more deaths and suffering.

Image courtesy of Tohoku University and Studio Xxingham

Image courtesy of Tohoku University and Studio Xxingham

How are power and ignorance intertwined?

People often say that knowledge is power—but ignorance can also be power. Ignorance influences what people do or don’t do, and its persistence can have profound consequences for society. For example, politicians and companies have used climate change denial to reinforce their power and protect their interests.

How does ignorance impact genders?

Ignorance is not distributed equally. For centuries, science has been dominated by men, and even today there are still major challenges in promoting greater representation for women. Until very recently, science knew comparatively little about women. For example, most medical research was conducted on men, leaving the effects of treatments on women relatively unknown. In this case, ignorance disproportionately disadvantaged women.

On the other hand, ignorance can sometimes advantage men. In Japan today, some men view the advancement of women as a form of “reverse discrimination.” Regardless of the merits of that argument, this view conveniently ignores the long history of discrimination against women. For women, ignorance often produces disadvantages; for men, ignorance can preserve privilege.

Moving away from your research, do you have any advice for young and aspiring academics?

My advice is to pay attention to the world around you. Fundamentally, academia is about solving problems that arise from society. Yet academics can easily end up in a bubble. Just as food nourishes us, the outside world can nourish new ways of thinking. This is why I write books as well as academic articles. Books are more accessible to the public, and agnotology connects closely with people’s everyday lives. I want my research to reach beyond the walls of academia because research is not just for academics.

Finally, what do you do to relax outside of the classroom?

I have recently developed a fascination with mushrooms. I like to look at them, gather them, and of course eat them! When I inevitably hit writer’s block, I take walks in nature to refresh my mind and spirit. Reading is also another way I relax. Sometimes, if I feel stuck in my own research, I will pick up an unrelated book—or even a difficult philosophy text—for inspiration.

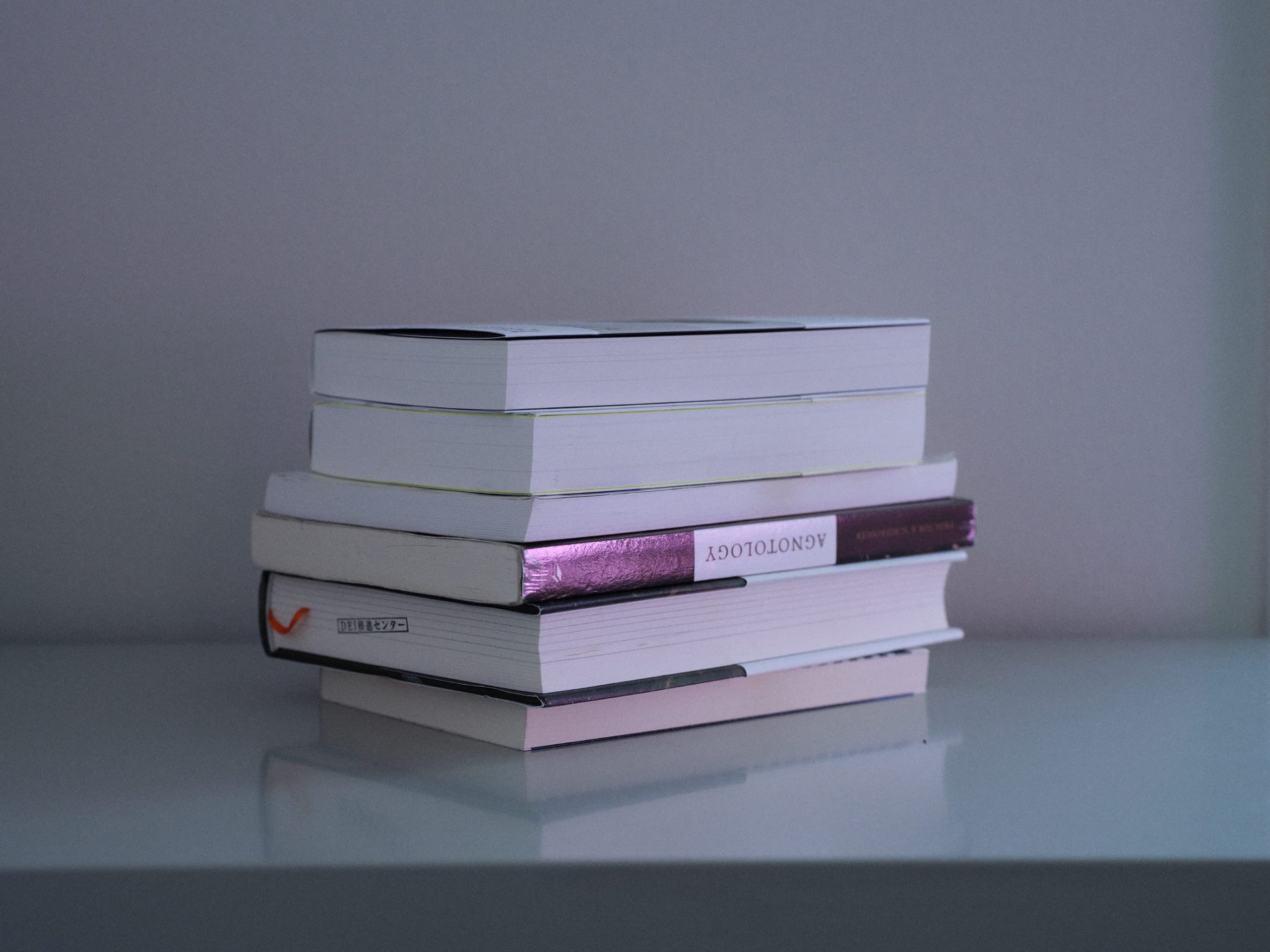

Photograph: A stack of selected works featuring agnotology. All but one include Soto Tsuruta's contribution as author, editor, or translator.

Born in Tokyo, Soto Tsuruta’s research explores how knowledge—and ignorance—shape the ways humans relate to nature and technology. He has played a key role in bringing the ideas of agnotology and gendered innovations to Japan, co-editing The Potential of Gendered Innovations (2024) and Invitation to Agnotology (2025), as well as co-translating Londa Schiebinger's Secret Cures of Slaves (2024). He currently serves as Specially Appointed Assistant Professor at Tohoku University’s Center for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, alongside roles at Ochanomizu and Osaka universities.

Passionate about connecting science and society, Tsuruta has organized reading groups, science cafés, and public lectures since getting his master’s from the University of Tokyo. His current work looks at the challenges of the “post-truth” era—when people tend to prioritize emotions or political beliefs over facts and truth—and how human knowledge (and ignorance) of wild plants has shifted over time. He is also developing several new book projects that continue his mission to spark fresh ways of thinking about science, society, and the stories we tell about them.

Tohoku University Declaration of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

https://dei.tohoku.ac.jp/en/

Romance

of

Research