In line with the 10th anniversary of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, the Architecture and Urban Design for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience initiative (ArcDR³) held its second forum on March 6, which focused on "Learning from Tohoku."

The forum comprised three themed panels, each featuring a main lecture by a Tohoku University professor, followed by a discussion among panelists from ArcDR³'s 11 participating universities.

Haruka Tsukuda, from the Department of Architecture and Building Science, kicked things off with a lecture on "Housing and Community Recovery."

An estimated 400,000 homes were destroyed or damaged in the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, she said, and the region faced significant challenges during reconstruction. Among them, an aging population, and the traditional style and locality of the housing. With new construction prohibited in tsunami hazard areas after 2011, Tsukuda said that the residents' transition from rural to urban living became an important focal point in the building of disaster public housing.

She spoke of the threat of isolation in these new urban surroundings, and cited examples of "solitary deaths" in disaster public housing after the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995. "The residents in the disaster public housing were in large, high rise buildings separated from their previous communities," she said. "Furthermore, the apartment-style units were closed off, so they were isolated from public spaces."

In the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, experts like Tsukuda advised local governments to adopt a more community-friendly plan for disaster public housing, such as having the living room face a common area. "In this type of unit, residents can communicate easily with their neighbours," said Tsukuda. "Because this plan is similar to a traditional house in a fishing village, we think that residents can continue to live in the way they were used to before the earthquake."

In the discussion that followed, the panelists talked about strategies for building community ties and transforming architecture to enable communities to be connected.

The second theme was "Infrastructure Recovery," led by Shunichi Koshimura of the International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS).

He began with a series of numbers which he described as "the characterizing statistics of tsunami disasters." Specifically - 58 tsunamis caused some 260,000 deaths in the past 100 years. "What these stats show is that destructive tsunamis are very rare events," he said. "But when they occur, they cause huge devastation to our society."

Following the 2011 tsunami, Sendai City incorporated multi-layer protection measures against future disasters. According to Koshimura, this included a seawall on the coast as the first line of defense, a coastal forest and, behind that, evacuation facilities near residential areas. But, he warned, coastal infrastructure is no guarantee of protection and "even great seawalls can fail."

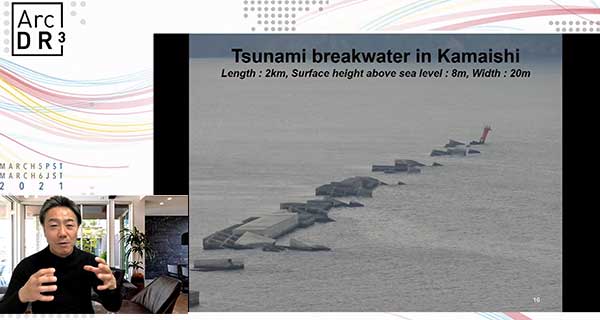

Kamaishi city in Iwate had what was once regarded as the world's largest breakwater, a huge concrete structure 8 meters above sea level. "Before 2011, we believed it would protect us, on the assumption that no tsunami would ever top it. But the 2011 tsunami did. It attacked the seawall until it collapsed and overturned."

The panel discussed the dangers of complacency, and how even computer simulations and tsunami hazard maps have limits to what they can predict.

Perhaps the most emotional panel of the day was the last one, when Masashige Motoe, from the Department of Architecture and Building Science, spoke on "Disaster and Memorialization."

He mentioned the infamous ship, Kyotokumaru #18, that got swept inland from the port of Kesennuma. Despite being one of the most enduring images of the tsunami, the ship was eventually dismantled because local residents found the sight too painful. "Disasters are harsh experiences that we try to forget," he said. "But when we do that, we also forget to learn the lessons."

In Minamisanriku, another enduring image - a red, 3-storey disaster management office that was engulfed by the tsunami - has been preserved as a legacy of the disaster. Forty-three staff members died that day, including the ones making the critical life-saving evacuation announcements. A park has been built around the remains of the building. "The remains of a disaster can be a very political space, what should be left and what should be lost," said Motoe.

For Tohoku residents, the most famous remains, are the devastated elementary schools along the Miyagi coast.

Okawa Elementary School in Ishinomaki was hit by a tsunami that came up unexpectedly from a nearby river. Seventy-four children and 10 teachers died that day because they were not able to escape, despite there being a mountain nearby. It was one of the biggest tragedies of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, and the school has been preserved as a legacy of the disaster. "Many people visit Okawa Elementary School and they are at a loss for words," said Motoe.

The other school that has become synonymous with the tsunami's impact on the coastal communities, is Nakahama Elementary School in Yamamoto town. There were 90 students, teachers and residents in the school that day. When the principal heard the tsunami warning after the earthquake, he decided not to go to the designated evacuation site, and sent everyone to the roof of the building instead. A 10m high tsunami, hit the school and destroyed its first two floors. Fortunately everyone on the roof survived.

Nakahama Elementary School has been open to the public as a memorial site since September 2020. Motoe was in charge of its design direction.

"A simple way to design this type of remains, would be to show the threat of earthquakes and tsunamis, and the events that took place," he said. "But as we listened to the stories of the survivors, the local people who built the school, the teachers and the town residents, we realised that there's so much more to the story we could share."

Motoe and his team secured the structure but left most of the devastation as it was. Visitors can enter the attic store room where the children spent the night, and view a model of the lost town in what used to be the school library. There's also a video showing an overview of the disaster.

"According to the guides, many visitors to Nakahama talk about their own disaster experiences after the tour. It's in contrast to Okawa Elementary School," said Motoe. "I think some disaster sites leave everyone speechless, while others make everyone want to talk and share a part of themselves. I believe that both are necessary memory keepers for us."

Visibly moved by the lecture, the panel discussed how "collective memory" differs from history; and how a collection of personal experiences can function as a social framework to record an important event. "We need to design ways to collect memories the correct way," said Motoe.

Wrapping up the forum, Professor Hitoshi Abe of the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA, co-founder of ArcDR³ and an alumnus of Tohoku University, spoke of how the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami moved him. "I was in Los Angeles then but I grew up in Sendai. I watched many familiar places being destroyed by the tsunami on TV," he said. "In these last 10 years, it seems like the risk of disasters around the world has been increasing. I believe that what we are trying to achieve with architecture and urban design for disaster risk reduction and resiliency, is needed now more than ever."

ArcDR³ is a global partnership established in 2019 by IRIDeS at Tohoku University, xLAB at UCLA and Miraikan, the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation in Japan. The third ArcDR³ forum - titled "Manifestations of Regenerative Urbanism" - is scheduled to take place in November.

Link:

- ArcDR³ Initiative: https://xlab.aud.ucla.edu/irides-tohoku-arcdr3/

Contact:

Associate Professor Elizabeth Maly

International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS)

Tohoku University

Tel: +81 22-752-2153

Email: maly tohoku.ac.jp

tohoku.ac.jp