Unlocking the Secrets

of the Brain with Fibers

Curiosity is the driving force behind everything we do

Your current research focuses on multifunctional fibers. Could you tell us what these fibers can do?

To understand how the brain truly works, we need tools that can probe its activity with exceptional precision.

When I first started my lab, I wanted to advance the multifunctional fibers I had developed during my PhD studies. These fibers are engineered to interact with the brain in innovative ways. They can optically stimulate neurons, record electrical signals, and deliver drugs through microscopic fluidic channels to influence neuronal behavior.

Over time, we have expanded their capabilities. The fibers can now perform magnetic and plasma stimulation, and even mechanical actuation, allowing them to move subtly within the tissue. Each function offers a new window into the brain’s complex communication systems.

The fibers sound like the ultimate interface. What are you aiming to achieve with this technology?

We want to create tools that allow us to interact with the brain as naturally and precisely as possible. The brain communicates using electrical, chemical, and mechanical signals all at once. Our goal is to design fibers that can both sense and modulate these different types of communication in real time.

By doing so, we can better understand brain function, and eventually, we hope, contribute to technologies that help treat neurological or psychiatric disorders. Ultimately, our goal is to create fibers that integrate seamlessly with our brain and other biological systems, enabling deeper insights into how the brain operates.

Does this mean this technology can be applied beyond the brain?

Yes, we are now exploring wearable applications by weaving fibers into textiles. These “smart fabrics” can analyze biological signals such as sweat or muscle activity. By studying the data from both the body and the brain, we can begin to understand brain–body interactions, such as how our physical states influence our mental states, and vice versa.

We believe that looking beyond the brain itself can give us a more complete picture of human physiology.

How did your journey with fibers begin?

My journey started during my PhD, when I was studying neurons and developing fibers to record their activity. We were investigating neuronal behaviors associated with anxiety and psychiatric disorders. During that time, we discovered another type of cell called astrocytes.

Astrocytes do not have electrical activity like neurons, so they were long overlooked. But new imaging tools, such as calcium indicators, revealed that astrocytes are deeply involved in neuronal communication and may play important roles in psychiatric disorders. They are often called the “glue” of the brain.

This discovery made me realize that to study such complex cellular interactions, we needed better tools, specifically, tools capable of comprehensively measuring and manipulating multidimensional signals, including electrical, chemical, and optical signals, across the diverse cell types in the brain, such as neurons and astrocytes. That realization brought me back to engineering.

So, astrocyte research inspired your transition toward developing new technologies?

Exactly. When I first studied astrocytes, I used optogenetic tools to manipulate their activity. But those tools were originally designed for neurons, and astrocytes do not function in the same way. They do not fire electrical signals.

This made me think we need technologies that are designed for biology itself, not adapted from somewhere else. That’s when I started developing multifunctional fibers — tools that could naturally match the way the brain communicates.

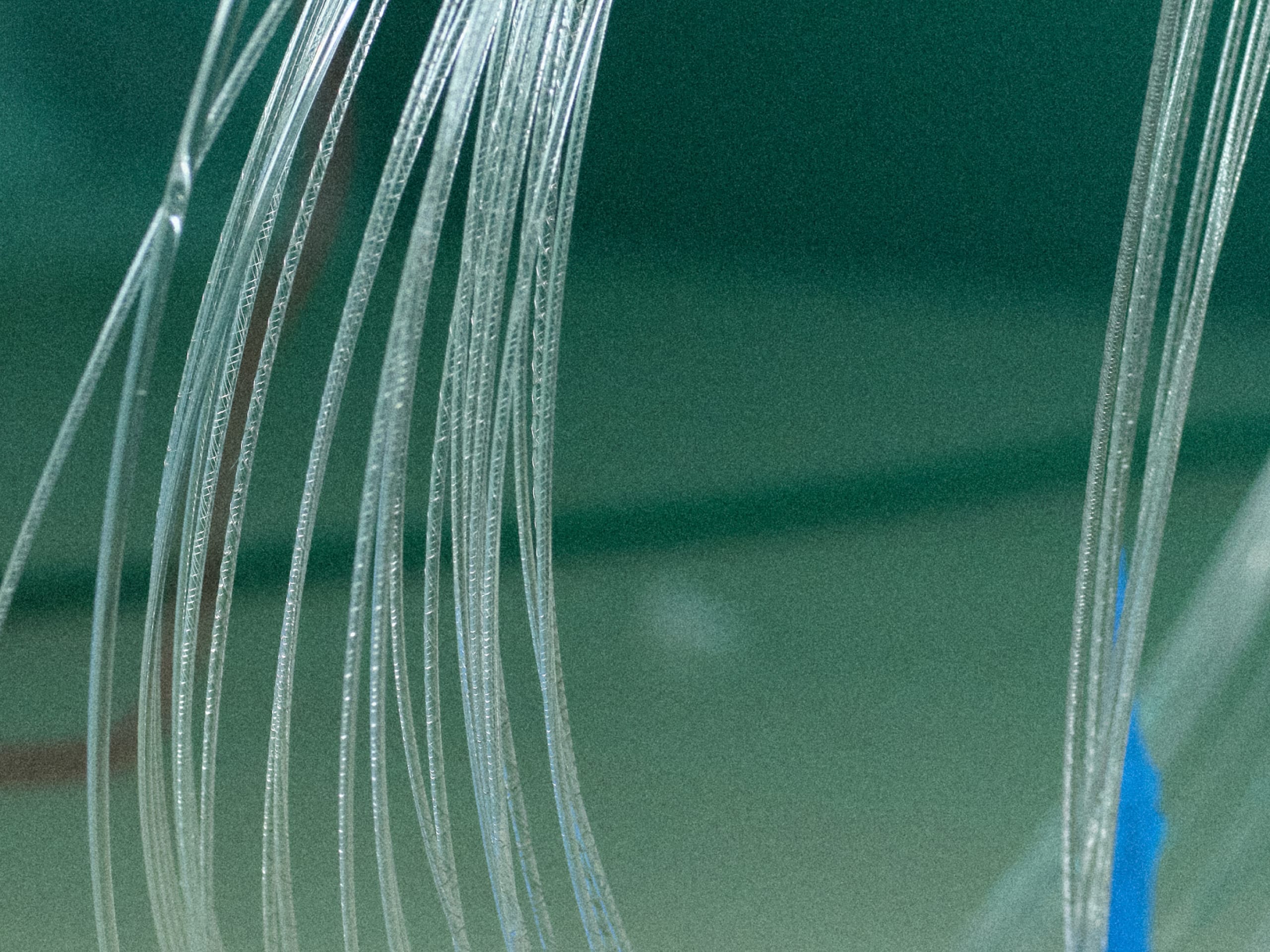

Image courtesy of Tohoku University and Studio Xxingham

Image courtesy of Tohoku University and Studio Xxingham

FRIS is known for its interdisciplinary environment. How has this shaped your fiber research?

After eight years at FRIS, I can definitely say that it provides an amazing environment where creativity flourishes. FRIS brings together researchers from engineering, materials science, biology, and physics. Such an interdisciplinary environment generates a sense of open-minded and endless curiosity. Even if working with other professors does not lead to direct collaboration, simple hallway conversations can generate new ideas.

One great example is the microcoils on our fibers that enable magnetic stimulation. It began with a basic question: could we make micro-spiral patterns inside fibers? Once we succeeded, we realized those spirals could act as magnetic coils. We then collaborated with colleagues at FRIS who study neuronal cultures, and the results were very promising. That project started only last year. Now we are preparing for in vivo studies and applying for long-term funding for the project.

The microcoil fibers sound fascinating. What’s next for them?

I’m very excited about them. They’re intricate structures that are both scientifically and aesthetically striking. The technology is patented, and several companies have already shown strong interest.

In addition, we are collaborating with researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) to explore the sleeping patterns of octopuses. One of my collaborators has discovered that, like humans, these fascinating creatures experience deep and shallow sleep. But unlike humans, Octopuses’ skin change color depending on if they are dreaming or not. We want to see whether our microcoils can help us understand or even modulate this fascinating behavior.

What keeps you motivated in your research, and what advice would you give to young scientists?

Curiosity is the driving force behind everything we do. Even when experiments fail, curiosity keeps us learning and moving forward.

My advice to young researchers is to find your passion and never give up. Keep trying, especially while you’re young and open-minded. As we get older, we can sometimes become fixed in our thinking. But discovery requires flexibility and curiosity. Those are the keys to innovation.

Outside of the lab, what do you like to do to unwind?

In summer, I like to go surfing, and in winter, I enjoy hitting the slopes for some skiing or snowboarding.

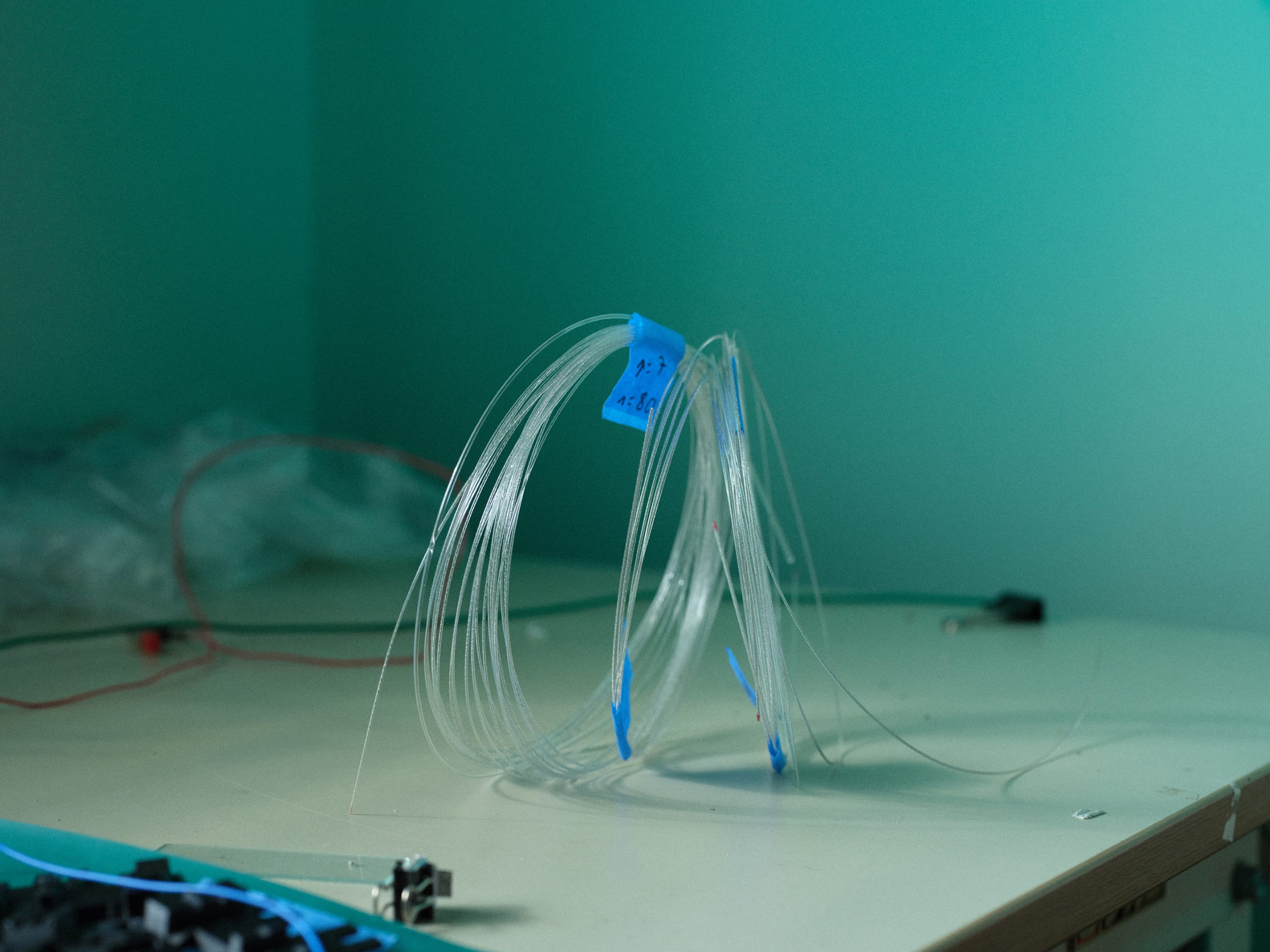

Photograph: A bundle of ultra-thin multifunctional fibers.

Yuanyuan Guo develops cutting-edge technologies to reveal the brain’s inner workings. Drawing on the thermal drawing process traditionally used for optical fibers, she helped create ultra-thin, flexible multifunctional fibers during her graduate work at MIT, Virginia Tech, and Tohoku University. These hair-sized devices integrate optical, electrical, and chemical modalities, which, when combined with field-effect biochemical sensors, enable unprecedented deep-brain imaging and multimodal neural interrogation.

At FRIS, Guo is dedicated to advancing fiber-based multimodal systems across in vitro, in vivo, and wearable applications. Beyond developing multimodal fiber-based neural interfaces for fundamental neuroscience, she collaborates closely with medical clinicians to potentially translate these technologies into practical medical tools. She is also exploring the integration of functional fibers into textiles to enable real-time sensing and modulation of human biosignals. At the microscale, Guo is pioneering a new class of fiber devices that contain their own internal analytical platforms, that is, “Lab-in-Fiber” systems capable of manipulating biofluids for high-precision bioanalytical applications. Through these efforts, her research aims to establish biofibertronics as a new interdisciplinary field that uses multifunctional fibers to interface with biological systems across multiple domains.

Romance

of

Research